1.

There’s a little store between the Nativity Church and the Mosque of Omar called the Shop of John the Baptist. There, I finally spot a postcard of Bethlehem to send back home. Most I’ve seen are of Jerusalem, most I’ve seen are of al-Quds.

“Qadesh?” I ask in my best Arabic. How much?

“One shekel.”

The store is run by Yahya, whose name is pronounced John in English. He introduces me to his friends Mohammed and Josef. They ask if I am Arab, and I say no, I’m Guatemalan. “Do you know Guatemala?” I ask.

Mohammed nods. “It’s very poor.”

They ask about my name. “Quiquivix is an Indigenous last name,” I share. “How do you say ‘Indigenous’ in Arabic?”

“What is that you mean?” they ask.

“You know, the Brown people who the White people kill, like in America.”

“Ah,” says Josef, “al-Naas al-Asliyeen, the First Peoples.”

“Not here!” Yahya hugs Mohammad. “Look, he is my brother. He is Muslim. I am Christian. We are brothers!”

I nod, “We have a lot to learn from you.”

“Yes, if everyone learns from Palestinians, there will be peace in the world,” Yahya says and everyone agrees.

They ask what brings me to Palestine. “I’m researching Palestine’s maps and borders,” I reply. “And learning Arabic.”

I hand Yahya one shekel for the Bethlehem postcard, say thank you, and start to head out.

“Come back,” Yahya says. “You want to sit? We help you with your Arabic homework.”

“Thank you, I will return inshallah,” I reply. If God wills it. A phrase I’ve always known in Spanish to be pronounced as ojalá.

2.

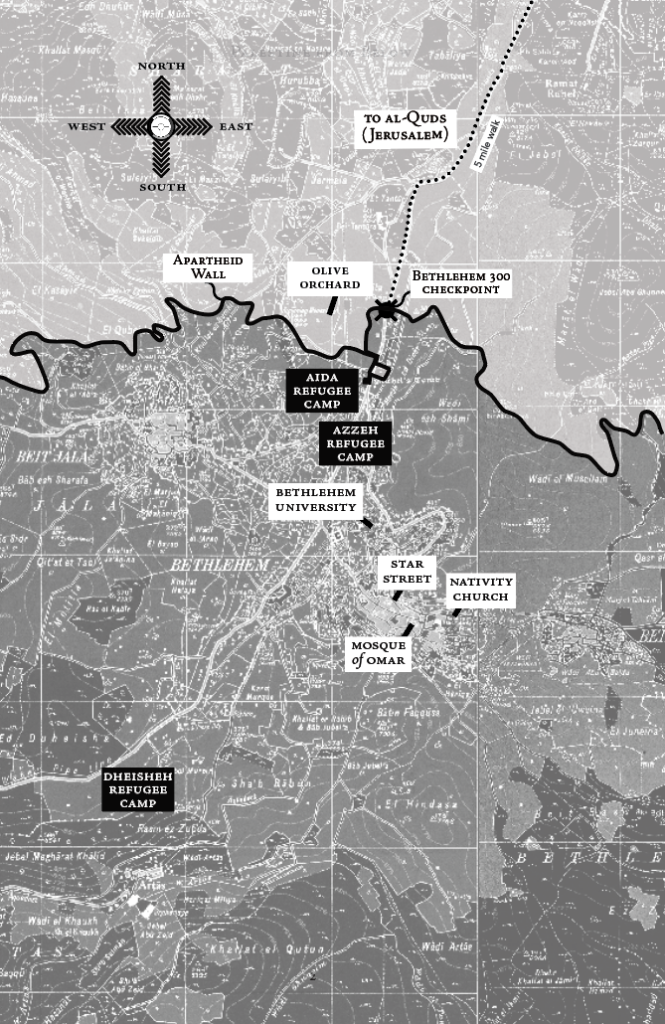

My Arabic teacher Khalil is drawing on the board the long and winding road to get to Ram Allah (“God’s Height”) from where we are in Beit Lahm (“the House of Meat”), a little town pronounced in English as Bethlehem.

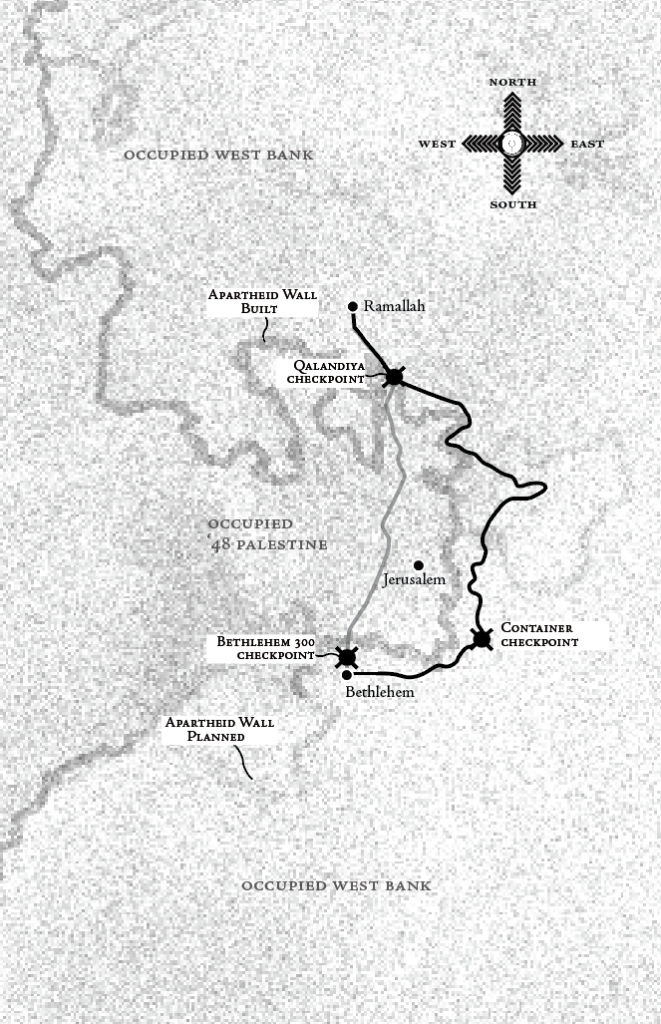

The State of Israel forbids most Palestinians in the West Bank from traveling on the straight road through the sacred city between Bethlehem and Ramallah, a city known as al-Quds (“the Holy One”), a city known in English as Jerusalem.

al-Quds is only five miles away from Bethlehem and then from there, only eight more miles to Ramallah.

“You have to go through Wadi al-Nar,” the Valley of Fire, Khalil points to the irrational, winding journey on the board, “cross the Container Checkpoint…”

“I think I’m going to be sick…” I find myself saying out loud.

“QiQi, if you want to live with the people you have to be like the people,” Khalil tells me, disappointed.

I am grateful for his reminder.

3.

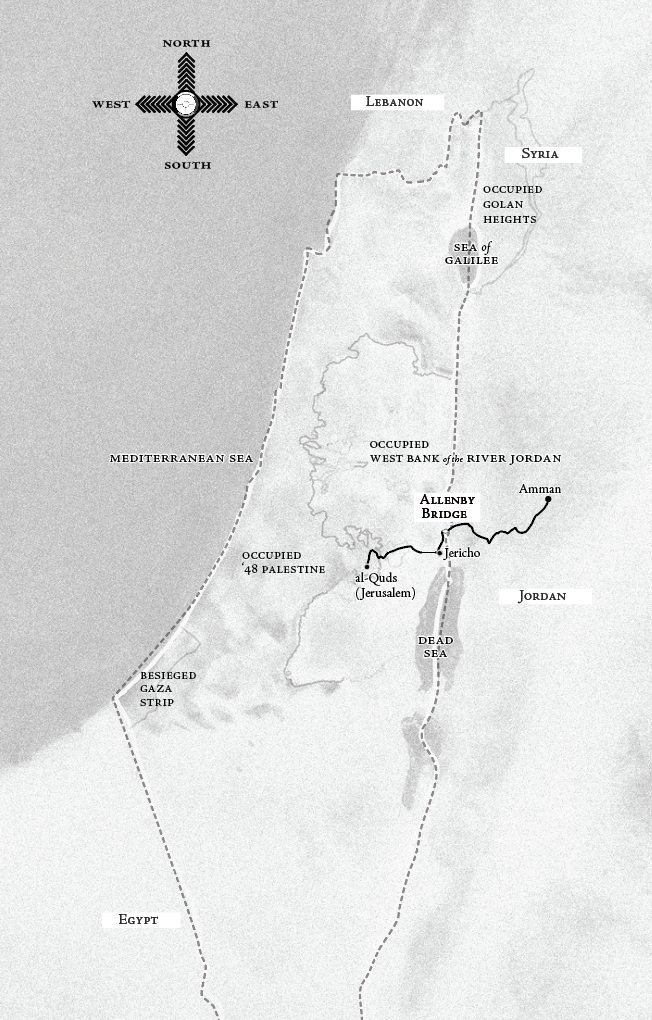

Crossing the border into the West Bank from Jordan means crossing the River Jordan near Jericho, on a bridge named after the soldier who captured Jerusalem for the British Empire in 1917 in a war the Empire called the “Peaceful Crusade.” “Peaceful” is a word fascists often use to mean peaceful only for them. The State of Israel controls all of Palestine’s entry points, and foreigners empathizing with Palestinians are often turned away. I wondered how it would go for me this time.

The soldier’s first question, always their first question, “Where is your father’s name from?” was to make sure I’m not Palestinian.

“Mexico,” I answered. The soldier smiled at “Mexico.” I was grateful I had thought to stop answering their questions with “Guatemala.” The soldiers never know Guatemala, and they don’t like it when you teach them.

The soldier seemed fine that I was going to Bethlehem along with Jerusalem to research “Holy Land maps of the nineteenth century made by American and other Western Christians.” I had practiced that, how to describe my doctoral research to Them without once referencing Palestine or the colonial present and be denied entry.

“Do you know anyone in Jerusalem?” the soldier asked. I gave the name of my colleague’s sister who lives in Malha. I had only met her once, at his wedding, but he told me to mention her and to pronounce Malha in a Hebrew accent.

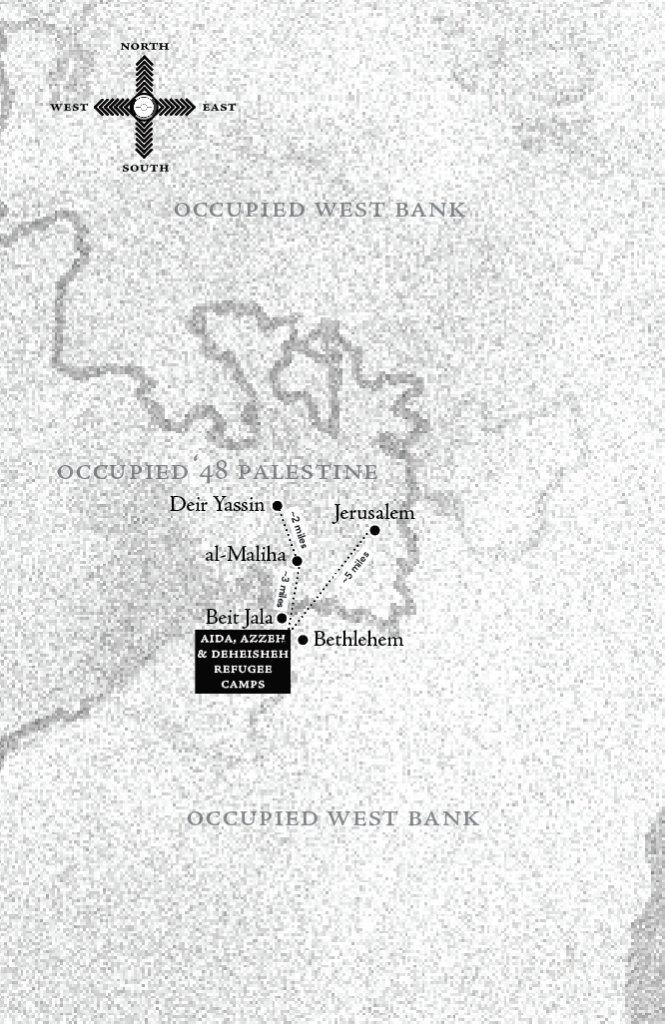

Malha is an Israeli settlement southwest of al-Quds, built on the remains of a Palestinian village, al-Maliha, “the Salted One,” who they say is named after the spring in the village that contains salty water.

Al-Maliha was ethnically cleansed of Palestinians by Zionist paramilitaries during the Nakba, the Catastrophe of 1948 that resulted in the creation of the State of Israel through the erasure of Palestine and the expulsion of Palestinians. After learning about the Zionist massacre of Palestinians in the neighboring village of Deir Yassin, the people of al-Maliha had fled for safety, assuming, as many Palestinians who did the same during the Nakba, they would return home once the war ended. The war hasn’t yet ended. Both Deir Yassin and al-Maliha had signed non-aggression treaties with the Haganah, the Zionist paramilitary that became the regular military, the now badly named Israel Defense Forces (IDF). “Defense” is a word that fascists also like to misuse.

In its prior formation as the Haganah, the IDF signed treaties with Palestinian villages during the Nakba like they did with Deir Yassin, but a different Zionist paramilitary, the Irgun, massacred Deir Yassin villagers nevertheless and attacked al-Maliha a few days later, leading its people to flee, many toward Bethlehem and to neighboring Beit Jala, a name that means “Home of the Grass Carpet” in Aramaic, the language of Jesus of Nazareth.

Generations after the Nakba, many of al-Maliha’s people are still living in Bethlehem and Beit Jala, still as refugees, many still in refugee camps, not giving up on the return home. There are three refugee camps in Bethlehem created by the Nakba: Aida, Azzeh, and Dheisheh. Some of al-Maliha’s people live in Aida Camp. Some of their homes were taken over by Israeli settlers who still live in them today. Other homes in al-Maliha, the State of Israel completely destroyed.

Israel’s Malha today is one of the more upscale colonies, with a soccer stadium, a hi-tech industrial park, and a zoo. They say its indoor shopping mall was the largest in the Middle East when it opened in 1993, before the days of Dubai.

Israel’s Malha sounds like many places in the United States, meaning it’s easy to shop and be distracted from the blood under one’s feet.

Only a couple more questions and the soldier let me in.

Palestine.

4.

When we were little, our grandmother used to get angry at the telenovelas, at the musalsalaat in Arabic, at the soap operas, as they call them in English. She’d get upset whenever the good character died a tragic death and evil lived past the final episode, which happened a lot. “Hierba mala nunca muere,” she’d announce to everyone in the room. Bad weeds never die. She would sometimes add, Dios tarda pero nunca olvida, God takes a while but never forgets.

Israel’s Ariel Sharon is a hierba mala que nunca muere. An asshole that never dies. My mother, a sweet lady who cusses really nice would have nightly called him un maldito desgraciado, a fucking disgrace, all before the first commercial break.

In 1982, Ariel Sharon, Israel’s war minister at the time, helped orchestrate the slaughter of thousands of defenseless Palestinian refugees living since the Nakba in Sabra and Shatila Refugee Camps up in Beirut. It was a collaboration between the fascists of Israel and the fascists of Lebanon.

The Sabra and Shatila Massacre revealed to many that Israel is the aggressor, not the victim, tarnishing its reputation. The backlash led Israel to conduct something to resemble an internal investigation, finding Ariel Sharon responsible, dismissing him as Defense Minister, demanding he never hold public office, then voting him in years later as Prime Minister.

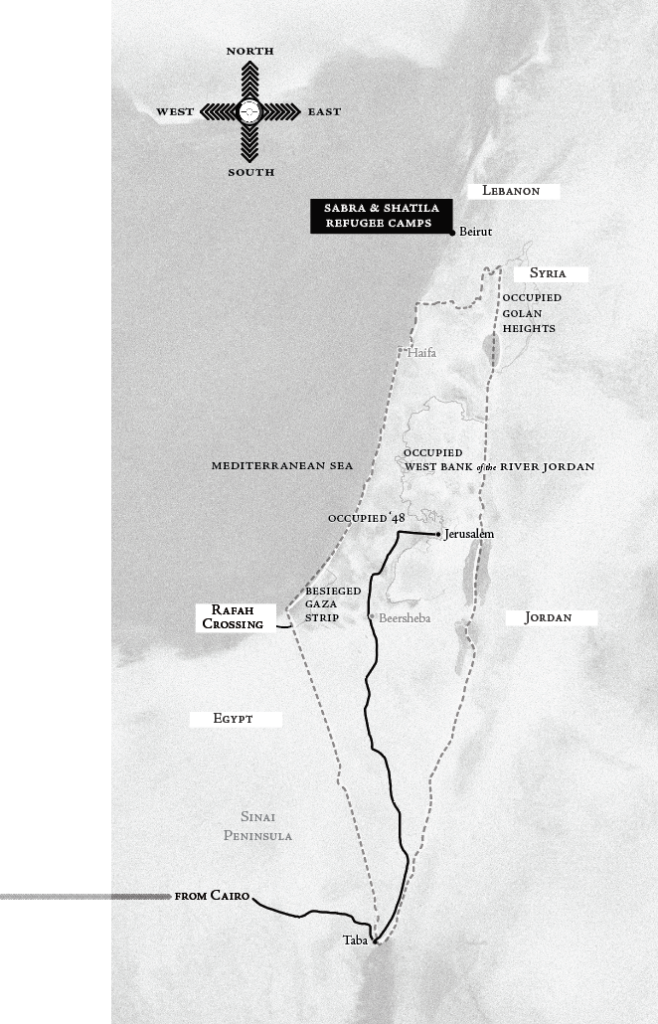

The first time I had the honor of touching Palestine’s soil and encountering her people was four and a half years prior. As our bus was crossing the Sinai Peninsula from Cairo toward the border at Taba, we were all learning Ariel Sharon had just suffered a stroke. That day was January 4, 2006.

It is now the year 2010 and Ariel Sharon is still alive, in a coma being kept alive, in a permanent vegetative state. Hierba mala nunca muere, I hear my grandmother say.

5.

I can’t stop staring at two-year-old Little Nellie, listening to her teta Mary, her grandmother, tell her a lot of things in Arabic I cannot understand but Little Nellie seems to fully grasp. I have been studying Arabic longer than you’ve been alive, habibti, querida, darling, and you understand a million times more.

I am renting a room from Mary for three months before I go off on my own. Mary and three generations of her family live on Star Street, steps away from the Nativity Church, the Mosque of Omar, Manger Square, and three refugee camps.

They say conversation and repetition are important when learning a new language. I feel this must be true. Over the past two weeks I have engaged in the following conversation with Palestinians so much, I don’t have to think before replying anymore:

“Min ween inti?” Where are you from?

“Amreeka.”

“Inti arabiyeh?” Are you Arab?

“La’, min asl guatemalee.” No, I’m Guatemalan.

Right about here is where they pause, give a sweet chuckle, and gesture to their own face.

“Ana bashbah arabiyeh?” I offer. Do I look Arab?

They nod and immediately transition into fluent English, one of several languages every Palestinian in Bethlehem seems to know.

“You studying Arabic?” they ask.

“Na’am.” Yes, I reply.

“Al-Arabi sa’eb.” Arabic is difficult, they warn.

“Na’am.” Arabic is sa’eb indeed, I nod.

Saif, who runs a textbook store, tells me that his father, Allah Yerhamo, may God have mercy on his soul, used to say that you’re not a man unless you know two languages.

I have encountered Saif, whose name means “sword”, in my search for a first-grade textbook in Arabic, aiming to keep up with the six-year-olds of Palestine by the time I return home.

“And when you know four languages,” Saif continues, “that’s when you become a real man.” He apologizes for the gendered life advice. It confirms my suspicions that no Palestinian is impressed that I speak two languages fluently, so I’m going to stop mentioning it. Who does impress Palestinians is the priest everyone keeps bringing up who knows no less than eleven languages—No! Twelve. There’s a debate.

“Here, take this dictionary,” Saif suggests as I’m about to leave. “Al-Arabi sa’eb.” Arabic is difficult.

6.

On Star Street lives a little girl who speaks Arabic, English, and Spanish all in the same sentence. Her name is Suad, which means “happy.” She’s getting confused, her mother says and asks Suad to pick one language.

I introduce myself. Suad’s mother, Maria, is from Chile and is Christian. Suad’s father, Sameer, is from Bethlehem and is Muslim. They’ve been living in Bethlehem together for five years but will probably move to Chile in January or February. Sameer is having trouble finding paid work, and Chile might be easier. It has the largest Palestinian community outside the Middle East, many of whom are from Bethlehem and Beit Jala.

Maria says she doesn’t leave the house much and is happy to have company over. We are sitting on the roof of their building, and the view of Palestinian homes, church bells, and mosque minarets along the rolling hills is breathtaking. And then an Israeli settlement looking like a spaceship has landed on a mountain top breaks up the landscape.

Maria, Sameer, and Suad’s house is the only Muslim house on all of Star Street, they share with me. Sameer excuses himself to pray, and I ask Maria what it’s like in a mixed marriage where she’s Christian and he’s Muslim. She says Sameer is really good about it and doesn’t mind at all that she and Suad go to church.

I learned from Sameer how Suad speaks three different languages all in one sentence: he also speaks Arabic, English, and Spanish all in one sentence. I like listening to Sameer. He speaks about reality, about racism and genocide around the world and throughout history, to which Maria responds, “Sameer, pareces al Che con esa platica de comunismo,” Sameer, you sound like Che with all that communism talk.

“No es cosa de comunismo,” Sameer replies. It’s nothing to do with communism. “Es cosa de imperialism, khalas.” It has to do with imperialism, period.

7.

I’ve started watching the musalsalaat in Arabic with Mary and her daughter Lucy, who watch soap operas every night. The overacting helps me understand the Arabic sometimes, but the topics can be difficult.

The other night on the soap opera, for example, the working-class Suzanne sat her mother down for some shattering news about her relationship with the upper-class Ziad, whom she had been lying to about her socio-economic status. In that night’s episode, Suzanne had just returned from the doctor and shared some news that caused her mother to faint. It’s how I learned to say “I’m pregnant.” Ana haamel, she had said. Suzanne then announced at the dinner table to the rest of the family that she was haamel. One brother erupted, chasing a screaming Suzanne into the kitchen, their mother and younger sister chasing after him. The other brother remained seated, stunned. Then, without saying one word, he got up, grabbed a butcher knife, and stuck it into Suzanne’s stomach! “Ya haraam!” Mary exclaimed at the television. Something evil or sinful had just occurred. This had never happened before in my grandmother’s telenovelas. The episode ended and we turned off the TV. It was time for bed.

The next morning, I sat with Mary in her little store. She sells eggs, candy, soda, milk, chips, bread, toiletries, alcohol, and cigarettes. A lot of cigarettes. The neighbors are the best part about the store. Sometimes they come inside, say their hellos, and end up sitting in one of the chairs Mary keeps out. They stay for 10 minutes, sometimes an hour. When they leave, someone else comes to take their place.

The delivery guy was among the first this morning. He dropped off some soap, took a seat, and lit up a cigarette. He and Mary casually discussed things, I didn’t know what. Something to do with masaari, money. Then they started talking about me, which I could tell because they were looking at me. Where is she from? Is she Arab? Are you sure? She’s studying Arabic? Arabic is difficult.

After the delivery guy left, two tourist police officers came in. They took a seat, lit up a cigarette, asked who I was, where I was from, was I Arab, was I sure, Arabic is difficult.

After they left, a neighbor came into the store and sat down in a huff. She was fanning herself from both the heat outside and some sort of anxiety. The conversation started out politely. Good morning. How are you? I am fine thank you. Who is this? Where is she from? Is she Arab? Are you sure? Arabic isn’t too hard. She’s learning in Arabic script? Arabic is difficult.

Then the conversation’s speed and volume steadily increased. The neighbor became upset, and I could only catch a few familiar vocabulary words: banaat (daughters), masaari (money), majnoona (crazy, in the feminine form).

Mary could only reply intermittently, “La’! La’!” No! No! every time the neighbor paused for air.

This continued back and forth for a long time without me understanding a word for a while until I heard sharmouta, whore. I knew that word. Nadeem back home had taught me that word.

“Ya haraam! Ya haraam!” shouted Mary, almost falling from her seat. It upset everybody present for several more minutes until the conversation died down and the neighbor said her goodbyes. It was 11:30am, and it was time for lunch. Mary eats lunch at exactly 11:30am in front of a musalsal downstairs, and at exactly 12:30 noon she turns the television off and takes her siesta, her mid-day nap. It’s a non-negotiable schedule.

As Mary and I walked downstairs, I asked in English so it was clear I wouldn’t be imposing, “Is it okay if I sit with you in your store again?”

“Na’am habibti, na’am!” she exclaimed. Yes my darling, yes!

“Beheb ajles hon… hada zay musalsalaat.” I love sitting here… This is like the soap operas. “Musalsalaat haqeeqiya!” she laughed as we walked down the stairs. Real-life soap operas.

8.

Walking in the door tonight, I thought I smelled menudo. Tripe.

It was Sunday, a special day. It was special because Mary’s daughter, Nellie, after whom Little Nellie is named, had cooked karshaat, Arabic for tripe. I asked what the special occasion was, and Nellie replied that karshaat was the special occasion. The day becomes special because you have cooked karshaat.

I hadn’t heard of karshaat before, so I emailed Fayyad back home, whose mother Suhaila introduced me to many of my first Palestinian dishes up near Jenin on an earlier trip, in their village named Rummaneh, which means “pomegranate.”

When Suhaila had me taste a regional spice called za’atar, it was at her kitchen table when I decided I would name my first born Za’atar. Za’atar is a mixture of sumac, sesame seeds, olive oil, and either thyme or oregano that there’s a lively debate about and that I don’t get involved in.

I looked up karshaat and found an article in This Week in Palestine revealing that karshaat is cooked once or twice a year and is a highly ceremonious, intimate meal, and that Palestinians trust only the “ritual cleanliness” of their mother’s, sister’s, or wife’s kitchens. I showed the article to Nellie, and she confirmed it was correct. And that yes, there is no way she would ever eat karshaat at a restaurant, “It’s disgusting!”

Nellie had taken five days preparing this meal. Her sister Lucy shared that one reason Palestinians don’t usually invite foreigners to eat karshaat is because many react disgusted to eating tripe, an insulting response to such a special invitation. This explained why everyone in the living room had paused to look at me when I first walked in the house, awaiting my reaction to the scent of karshaat and looked relieved when I responded that it smelled like home. I was humbled at the invitation to enjoy karshaat with the family that night: tripe stuffed with lamb that swims in a yogurt soup made out of jmeed, hardened yogurt.

After dinner I rushed back to my email and saw Fayyad had already replied, “That’s awesome, I have not eaten karshaat in forever,” he wrote. “You’ll earn your stripes that way.”

9.

Sitting with Mary in her store again, I learn she was born in Bethlehem and was six years old at the time of the Nakba of 1948. Her father, sister, and brother were killed in Israel’s 1967 invasion of the West Bank, the so-called Six Day War. They were at Bethlehem University when Israel dropped a bomb right on top of them. Mary’s brother was also injured with gashes on his arm and leg. She was at home.

I ask Mary how her husband died. The Israelis killed him, right here in this house, she said. They came looking for their sons, teenagers during the First Intifada. Her husband went upstairs to answer the door when the soldiers buzzed. They beat him fatally on the head. He was in the hospital 21 days before he died. The year was 1990. The day was June 18.

Mary shows me a picture of her father. It is a wallet-sized black-and-white photograph with the ridges around the edges. He wore a light suit, a patterned tie, and a dark sweater vest. He had glasses, and his hair was combed back with few gray strands as highlights. Mary looks just like him.

Mary also points to a photograph of her husband. It is one I see every day, a color photo that hangs above the store register.

10.

I had an interview this morning for a volunteer position in Aida Camp’s Lajee Center. Everything I’ve heard about Lajee so far, I like. They don’t work with any of the political parties, and I don’t either. Lajee is looking for someone to host an art class with the kids. I only know a little Arabic, and Yousuf suggests that little kids are great to practice with. They love to teach adults, and when you mess up, instead of scold you they are eager to help.

I keep hearing the voice of Mayssun from Shatila Camp: The camp isn’t a zoo. Don’t be a foreigner asshole. Lajee seems to know this well. They sent another foreigner to size me up before I interacted with anyone else. Rich is a British photographer who has been working with Lajee for years. He didn’t seem thrilled to meet me and even seemed suspicious of me at first, which makes be think we’re going to get along.

Rich recently came out with a book about Aida Camp’s stories of struggle. At the end of my interview, he let me borrow his only copy. I promised to return it that evening at his book talk at the Peace Center in Manger Square.

Rich is different from other foreigners here. At his talk, he made something clear to everyone present: his book is made up of stories by Palestinian refugees about life as refugees, these aren’t “Richard’s adventures in Palestine.” When during the Question & Answer period someone asked about his plans for the future and how his work is coming along, he answered that he wasn’t there to talk about his personal life, but wanted to discuss Israeli apartheid, the failure of the international elites, and the inspiring resistance of the Palestinians.

As far as his plans for the future, he hopes to take Palestinians on a permanent trip back to Haifa and Jerusalem.

11.

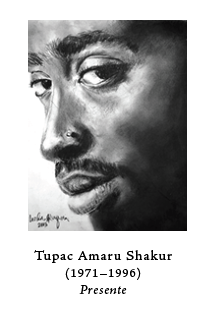

They say in Islam, it is forbidden to draw the human form so as to not contribute to idolatry. I am nervous about leading an art class. All I’ve ever known to draw is the human form. All I’ve mostly drawn is Tupac Shakur. At the entrance of Aida Camp’s Lajee Center, there’s a life-size charcoal sketch of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who makes me feel it will be alright. I consult with Mohammed about my limitations and he nods about the human form and Islamic art, but says it’s not a problem, there’s nothing I can’t teach the kids.

This was nice to hear, and my first day went well, and it’s true about little kids eager to help me with my Arabic. There were a couple of the older girls who misbehaved and reminded me of myself when I was their age and misbehaved with my mother. My Palestinian cholitas, the homegirls of the group, who I’m pretty sure were making fun of me for not knowing Arabic.

Todo se paga en esta vida, I heard my mother say. Everything is paid back in this life.

12.

Mohammed suggests that I not mention to anyone that I’m working at the Camp. He knows of instances where the jaysh, the IDF, has come into the camps and deported the foreigners, taking them straight to Ben Gurion Airport and out of the country.

Rich is less worried. He says if the jaysh comes, to just go about my business. Tell them I’m helping in a class, that I’m American. Khalas. That’s it.

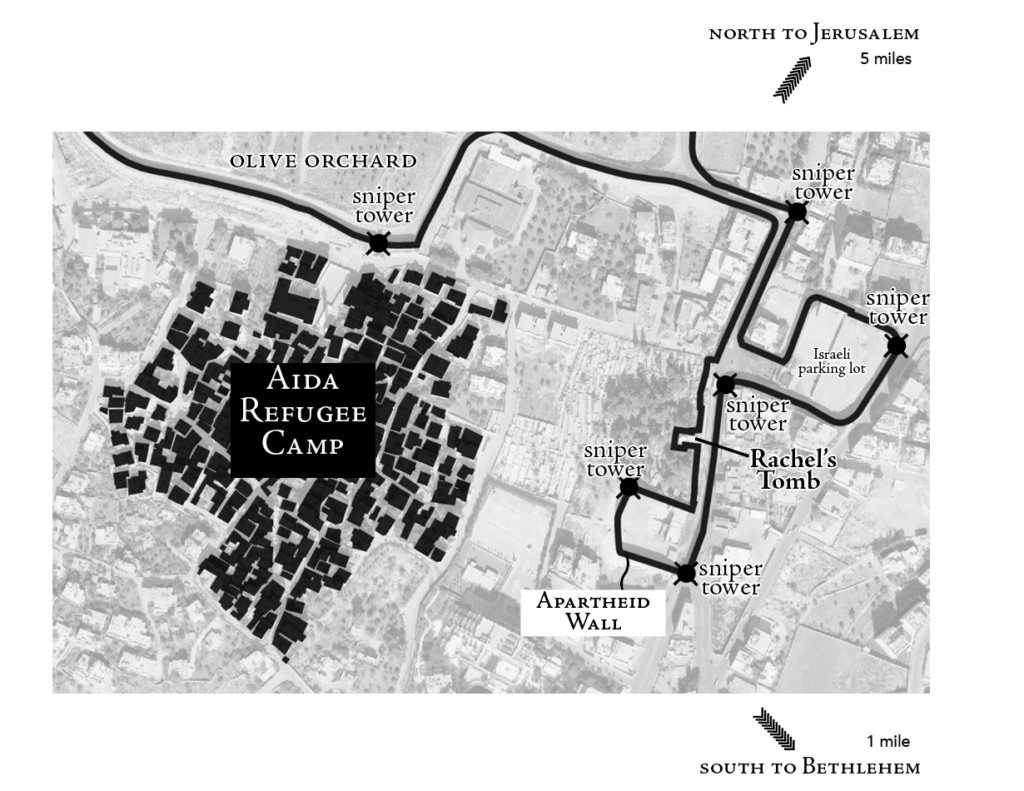

When I had first asked Rich what to do if the soldiers came, he had exclaimed, “RUN FOR YOUR LIFE!” We laughed, but there are bullet holes on Lajee’s front door and on the wall of the balcony where we were sitting, one right above Rich’s head. There are sniper towers surrounding the Camp; the Apartheid Wall is adjacent on two sides. Rich says they haven’t shot from there in a couple of years. Now they just come in on night raids and arrest people.

Tonight, the jaysh are out in Rachel’s Tomb, a Biblical site in the cemetery right next to Aida Camp and now an Israeli military base. The jaysh are on the roof of what used to be a Palestinian apartment building before Israel took it over. It’s the highest building in the area and serves as a lookout point for them. Rich thinks it may be a diplomatic meeting going on.

On Israel’s orders, the Palestinian jaysh, the Palestinian Authority (PA), are inside the Camp right now. When I first walked into Aida, I almost froze, thinking it was the Israelis.

Rich says that two years ago, people in the Camp started saying “Israeli jaysh” instead of just “jaysh” because it used to be assumed which jaysh everyone was talking about. But not anymore.

Mussa points out the Palestinian jaysh will shoot at Palestinians more quickly than the Israeli jaysh.

13.

In Arabic class tonight, Khalil asks if I want to know how to say anything in particular. I have been preparing a list. How do you say, “Black people continue to suffer in America under Barack Obama,” and how do you say, “functionary of the white-supremacist society.”

The word for functionary is the same as employee: muwazzaf, and the supremacist is al-ifadhalia, which has a shared root with “prefer.” Capitalism is rasmaliya which is two words: ras + mali (chief + money).

Khalil asks who is more racist (‘unsoori): the USA or France. He argues France, I argue the USA. He knows France. I know the USA. After exchanging notes, we decide in the end it’s a tie. From this debate, I learn Khalil likes Malcolm X.

Khalil also teaches me how to talk about maps. The map of historical Palestine is Falestin al-Tarikhiya. The maps of just the West Bank and Gaza are Falestin al-Siyasiya, political Palestine, but that’s not the true Palestine, he says, just the political one.

The true Palestine is the Falestin al-Tarikhiya that exists in the hearts and minds of all Palestinians.

14.

Nellie this morning tells me about her friend living in the USA who feels very lonely. People don’t know each other in the USA, her friend has accurately described. Everyone keeps to themselves.

Nellie’s friend has also been sharing about the foreclosure crisis and how people are losing their homes, often without anyone to take them in.

“Here,” Nellie says about Palestine, “If you’re hungry, you go to your neighbors for some bread.”

I nod. I share with Nellie that some people believe Palestine should become more like the USA.“Wala marra!” she exclaims. It’s how I learned and won’t ever forget how to say “Never!” in Arabic. Literally, “Not even once!”

Nellie shares more about her mother’s family in the 1967 invasion. She says the bomb dropped on Bethlehem University was the first bomb of the war. She also had a cousin killed in the First Intifada by a sniper while leaving mass at the Nativity Church. He was holding a two-year-old and dropped the baby, falling as if he was drunk. One bullet. She wants to show me where he was shot from, and I’m not going to believe it. It was from a hilltop, really far away.

Nellie’s friends often ask why she doesn’t leave Palestine, as life is so difficult here. She scoffs at the thought. “Wala marra! I will die in Palestine,” she exclaims. They can’t understand how Nellie’s not interested in making money elsewhere.

Nellie asks about my mom and dad, and I tell her the story. She is curious what my mom did after the divorce. “We moved in with my grandmother,” I reply.

“You are like Arab,” she says. She gets up to wash her coffee cup in the sink, then turns to me to say, “It warms my heart, the story of your mother.”

15.

I have just learned that Mahmoud, who is getting to know me as a regular at the Square Café in Manger Square, where they have the good Wi-Fi, also likes Malcolm X. When he was imprisoned in Israel’s dungeons for two-and-a-half years, he read the Autobiography in Arabic and cried, he says. Other Palestinian men share with me about times when they’ve cried. They share it without shame, just as a matter of fact. They make me believe it’s true what they say about revolution, that love is its defining characteristic.

Mahmoud is Muslim, and Khalil is Muslim, and Malcolm X was Muslim, el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. Wondering if Christians also know of him, I ask Nellie. She doesn’t know. But she does know who Che Guevara is. Everybody knows who Che Guevara is. His face and name are graffitied everywhere in Palestine. Here there are even children named Guevara.

Nellie chuckled when I first mentioned Che. She said that Lucy used to have a picture of him in her bedroom in a frame. One day during the First Intifada, Mary flew into a rage, took it down, and slammed it to break it. “Her husband had just been killed, her two sons were in jail…” Nellie explained. Revolution may be defined by love, but revolution is not romantic.

Incredibly, that same night on the musalsal before bed, the character of a young man whose rich father had abandoned him was wearing a Che Guevara sweater and had a Che Guevara picture on the wall. I cautiously asked Mary, “Does everyone here like Che Guevara?” She replied right away, “Na’am, na’am!” Yes, yes! laughing and nodding. And that was all she had to say about that.

16.

Older Palestinian Gentleman, OPG, walks straight into the Square Café to ask one of the servers, Khalil, something about Arafat and Ramallah. OPG then turns my way and asks in fluent English, “You know Arafat died today?” The day is November 11, 2010. Yasser Arafat was the President of the Palestinian Authority.

“How many years ago,” I ask. “Five? Six?”

“I don’t know, I don’t care, I never liked him.” He looks over his shoulder and whispers, “I don’t like any authority. None!”

He then peers into the kitchen searching for Khader, who everybody knows likes Arafat. The coast is clear.

OPG pulls up a seat at my table, lights a cigarette, and smoothly we move into shit-talking authoritarian regimes together, and not just some of them but about all of them, and how they need to go.

“It’s a dream!” he exclaims. He then reveals that when he was younger in the 1970s, he and his friends had pulled out a world map. They were going to move to an island and build themselves a country, inviting people from everywhere, a couple from France, a couple from here, a couple from there, very Noah’s Ark. But as they looked at the map for an island to move to, it occurred to them it was impossible.

“No island is truly an island?” I ask, recently defeated.

“Exactly,” he says. Not even Cuba is an island, we agree. No place will the empire leave you alone. Might as well fight where you are, where you know best, and with your people.

I ask OPG why he and his friend didn’t pick just Palestinians for their island home. He frowns, almost dropping his cigarette. He opens both hands, signaling the obvious. “Because we are all human.”

He gets up to leave. He says he has said too much, there are too many spies, and I might turn him into the Palestinian Authority.

Yalla bye!

17.

Some of the mothers in Aida Camp have put together a Palestinian cooking class to help raise some money for expenses. Everyone in the group has a family member with a disability, and before each class they collectively decide what to do with the money.

One time, they used it to take the children to a swimming pool in al-Khalil, a city pronounced Hebron in English, which means “friend of God,” so named after Abraham who is believed to be entombed there alongside his family at the al-Haram al-Ibrahimi, site of the Ibrahimi Mosque Massacre of 1994, where a Zionist from Brooklyn opened fire on praying Muslims, killing 29, many as young as 12 years old.

Abraham is the shared ancestor of all three Abrahamic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The empires of the West often like to leave out the Islam. The empires of the West used to also like to leave out the Judaism part in this shared kinship for a long time until the Zionist project made Judaism useful for empire, rather than fight against it. When the wretched of the earth become the wretched of the empire.

On this occasion, the mothers in Aida Refugee Camp will use the money to buy the children some clothes.

The class costs 60 shekels (about USD$20) each person, and includes a cooking lesson, the food, nice conversation, and a tour of the Camp. There are seven of us foreigners, plus a translator. Four have come down to Bethlehem from Ramallah. I don’t ask if they took Wadi al-Nar.

On this occasion, we are not getting to learn much cooking, but we are getting to eat well. They showed us the beginnings of things, but then shooed us into the living room and out of the kitchen. It was probably for the best. The food is delicious. The dessert is sweet semolina cake called basbussa, “bas” and “bossa” meaning “just” and “a kiss,” just a kiss. They serve us rice with thin pasta, a soup of spinach and chickpeas, and fried chicken.

One of the couples in our class is from Barcelona. I ask the husband, who is wearing a Barcelona soccer jersey, if his shirt gets him a lot of love in Palestine. “Yes!” he exclaims. Our translator, Mustafa, guesses that about 80% of Palestinians are Barcelona fans and thinks it has something to do with Barcelona being occupied, too. This upsets a woman from Brazil who says, “We have a great soccer team, and we were colonized too! All the Native people were killed…”

While at the table, we keep being asked if any of us have children. “Fil mustaqbal,” in the future, I answer, “inshallah.” One couple’s response is that they just got married and it’s too soon. Another couple says that maybe they will never have children. One woman announces she doesn’t want any children because there are too many people in this world and there’s not enough food. This almost halts the conversation into awkward silence. Palestinians have a lot of children.

“In Guatemala do they have a lot of children?” Mustafa asks.

“Yes, of course. It’s not a problem,” I answer.

One of the mothers says something Mustafa is eager to translate. “She says she has a casserole dish that can feed seventy.”

18.

The kids in our art class let me know right away they dislike drawing with charcoal. It’s not colorful enough. Last week I picked up the colored kind and have brought it to Aida Camp. The kids love it. I am thrilled the kids love it. They remark it is similar to tabaashir, chalk, and ask me where I got it and how much it cost. I tell them I got it in al-Quds, where each of the 15 pieces cost 6 shekels (USD$1.50) for a grand total of 90 shekels (over USD$22). They are stunned. “You can get 10 pieces of tabaashir for 1 shekel!” they exclaim. Colored and everything. They do the math together. I could have gotten 900 pieces of tabaashir with 90 shekels. They think maybe I got ripped off because I’m a foreigner.

After class they take me by the hand and walk me to a little store in the Camp that sells the 10 pieces of colored tabaashir for 1 shekel. Ammo Mohammad carries tabaashir in his store. He sits blocking the door and I can’t really see inside, but one of the kids squeezes through and brings out the tabaashir.

Ammo Mohammad is blessed to be a very old man with not a lot of teeth who loves to laugh and has energy for a lot of conversation. His English is really good, which I’m curious about but don’t ask. He wants to know about me, am I married, kids, why isn’t my husband here, to which the kids grab my hand and say, “Let’s go QiQi!” And it’s yalla bye.

19.

The tabaashir from Ammo Mohammad is a hit. We are drawing together on one big piece of paper, starting from the center out, all abstract shapes. While in shape-drawing mode I put two triangles together accidentally drawing what looks like a Star of David. Safa’ points out that is the jaysh’s symbol and shows me how to draw a five-pointed star instead. I apologize and thank her for that correction.

Today is Safa’s brother’s birthday, whose name is Anis. He is turning nine, and I draw him a birthday cake to celebrate the occasion and embrace it with his name in my best Arabic script.

The kids seem to really like this project and become protective of it when little 3-year-old Rand starts to draw on it like a 3-year-old would want to draw on it. They erase her contributions and ban her from the drawing, giving her a piece of paper to draw on instead. This makes her sad, so I put her on my lap and draw for her a Sponge Bob Square Pants waving the Palestinian flag, but there is no black charcoal around anymore, so I can’t color it in fully. I start to gift it to her, and she points out it’s not yet finished, the flag needs black on the top. I take my orders, successfully locating a black colored pencil.

Rachelle, a Mennonite from Canada also living in Bethlehem, stops by Lajee. We have become close friends since meeting a few months ago, each suspicious of the other at first. She is not with the Mennonites in the Yucatán deforesting the land. Also, she knows she’s a settler in Canada and needs to make right historical wrongs. It’s nice to have someone to constantly ask questions about Christianity where I don’t feel dumb and she doesn’t feel insulted. In my research on the “Political Mapping of Palestine,” I am having to read the Bible, which may seem obvious now, but I first learned about Palestine through secular writings, so reading the Book of Joshua hadn’t been on my list.

Rachelle has stopped by Aida today to purchase some of Lajee Center’s children’s books, drawn and photographed by the Camp’s children. She’s going to send the books home to help with the de-indoctrination of some family and friends.

I head to the sink to wash the chalk and hear Mohammad and Lajee’s director, Salah, speaking excitedly in the audio/visual room about Barcelona beating the crap out of Madrid last night, 5-0. Both Mohammed and Salah are big Barcelona fans and have been teasing the Madrid fans on the streets, waving at them with five fingers extended, “Hiiiii.”

Mohammad guesses that about 70% of Palestinians love Barcelona, and the other 30% love Madrid. Rachelle says it’s what’s led her to say she’s a Barcelona fan: whenever any kid asks, she has a higher probability of being right. I ask Mohammad what explains the love for Barcelona, and he says the same thing Mustafa said the other day. Catalonia, a region between France and Spain, holds Barcelona as its major city. “Catalonia is occupied by Spain and there is no place in the world that loves Palestinians more than Catalonia,” Mohammad ensures.

“More than Ireland?” I ask, surprised. He thinks about it and then replies, “They’re about even, actually.”

20.

It is February 2011, and day 12 of the Tahrir Square commune, the Egyptian people’s uprising and hopeful overthrow of their Zionist dictator, Hosni Mubarak. I am eager to hear my neighbors’ thoughts, but they don’t seem to want to talk about it. At least not to me. From these 12 days of scanning news and social media on my computer, my eyes are beginning to hurt.

There were solidarity protests for Egypt in Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jerusalem, and Nazareth. About 2,000 people were in Ramallah. There is a video circulating of a guy getting roughed up and arrested by the Palestinian Authority’s thugs. The Palestinian Authority, the PA, is a policing body made up of Palestinians that polices other Palestinians on behalf of Israel.

The PA was established with the badly named “peace process” that took place in Oslo, the capital of Norway. The PA is considered by many on the ground to be a collaborationist regime. The difficulty is the PA is heavily intertwined in the social fabric of the West Bank in terms of salaries and special privileges. The PA is fully allied with the Mubarak regime in Egypt and the surrounding regimes who are also being threatened with uprisings right now since the uprisings in Tunisia two months ago.

The PA has been known to regularly crush the protests in the West Bank supporting the resistance in Gaza, and now they’ve expanded their efforts to crush the protests supporting the Egyptian uprising.

I haven’t heard news of the numbers in solidarity with Egypt coming from Nazareth or Jerusalem. Bethlehem’s protest was in Manger Square. About twenty people showed up, almost all men, most with leather jackets and bellies that looked well-fed. The protest was mostly security. The demonstration had some Palestinian flags and later Egyptian flags. It lasted for about five minutes and khalas, that was it.

Rich was there photographing and gave up. He hates protests, he says. Most of the time they consist of journalists and Israelis, very few Palestinians. Generally, the protests are very small, but the journalists always get close-up shots making it look like there were a lot of people all around.

I gave up, too. I saw a few men arguing about what was going to be said at the protest, but I couldn’t understand. There were several people watching, keeping their distance all around the perimeter of the Square, but they didn’t join. Just watched.

I invited Rich for a coffee. He says everyone he’s been around is thrilled about the Egyptian revolution, a very different experience than I’ve been having. I ask how Aida Camp reacted to the Palestine Papers, the leaked meeting notes on the corrupt Oslo “peace process.” He says at first they thought they were fake and blamed Al Jazeera for publishing them, but by the third day they accepted they weren’t false. Time will tell what comes out of this realization.

Most of the shabaab in the camp, most of the youth in the camp, are Fatah party youth, but they make a distinction between Fatah and Mahmoud Abbas, the PA, and Salam Fayyad, who are part of Fatah. They hate all of them but still love Fatah. Mainly for what it used to be.

21.

Rachelle phoned this morning about a Unity Tent at Manger Square, the March 15 Movement. Near the Mosque of Omar is standing an olive-green tent with Hebrew writing on it. The tent looks like a refugee tent from old photographs. It has come from Dheisheh Camp, but nobody is sure if it’s from Nakba times. It doesn’t look old enough. About a dozen Palestinian youth are seated inside speaking to five tourists about the occupation.

A German young lady invites me inside and tells me about the March 15 Movement. The shabaab, the youth, have been spending the night in the tent. She and her sister are helping by pairing up with a Palestinian to recruit tourists from the Nativity Church to come inside the tent and listen to the demonstrators. “If it’s just a Palestinian who asks, the tourists probably won’t come,” she says.

There is a woman inside, a Palestinian Citizen of Israel, who just held a teach-in with Palestinian school children, describing the struggles of the Palestinians inside the part of Palestine Israel has been occupying since 1948, describing the struggles of the Palestinians “inside ‘48.” Everyone reports that the children sat listening intently to her the entire time.

They also report that because Palestinians in ‘48 speak fluent Hebrew in addition to fluent Arabic, she has translated the Hebrew writing on the tent: it is instructions on how to assemble the tent. Everyone laughs with a shared nervousness, with a shared relief. We don’t say much beyond that.

The Star of David and the Hebrew language trigger a lot of nervousness, even with me. I have to keep checking in with myself. It is what the soldiers wear, it is what the soldiers speak. I’m still trying to figure out how to talk about it. So far, it helps to learn it wasn’t always that way. For centuries, there existed Jewish people in Palestine who spoke Arabic until the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, which demands that no Jew can be a Palestinian and that to be a Jew is to be an Israeli.

Saoud, who speaks perfect English, is conducting a teach-in as I walk in. He shares about ending the division between Hamas and Fatah, and the possibility of a leaderless movement. I ask if he’s ever heard of the Zapatistas in Mexico. He says yes, he participated in a workshop a couple of years ago in Dheisheh Camp where American Indians came to connect anti-colonial struggles. From them, he learned about the Zapatistas. I tell him about the Zapatistas’ Festival of Dignified Rage during Israel’s war on Gaza two years ago, Operation Cast Lead, and how everyone kept bringing up the Palestinian struggle every day, and that the Zapatistas made a strong statement for Gaza. His face lights up. We coordinate for a teach-in on the Zapatistas.

I am curious about the larger March 15 Movement’s demands to dissolve the Oslo Accords and the PA. Saoud says he wasn’t speaking for everyone, and it’s not demanded as a group right now in the Manger Square sit-in, but he personally would like to see Oslo dissolved.

We say goodbye for now, and I head to Lajee Center and find Rich inside. He’s working on a new book project on Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions, BDS, and invites me tomorrow to a film screening in the Camp on South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle. They’re having the director come and speak.

I report to Rich that I just returned from Egypt to stamp out my passport and stamp back in, and have brought back a gift for Aida Camp, The Autobiography of Malcolm X in Arabic. He thinks it’s fantastic and we discuss showing the film to the shabaab and having discussion on the Black revolutionary movements inside the USA.

Mohammad walks in, upset about the March 15 Movement. It has been co-opted by the PA and Fatah, he reports. Also, why are people demonstrating in Manger Square? What’s needed is a demonstration against the occupation, not against God. The real protesters today didn’t go to Manger Square but headed to the checkpoint to throw rocks, he says. What’s really needed is 20,000 people to storm Qalandiya Checkpoint.

Rich replies that the sit-in is not all that useless. People are there talking about ideas and making their presence known. Even though protests are limited, they are still not a total waste. There is no movement in Palestine right now and it needs to begin somehow. How are we going to get 20,000 to storm Qalandiya overnight? Egypt was 30 years in the making.

As the conversation winds down, I ask Mohammad if we can look at the aerial photograph of Aida we were able to get. He spends some time getting oriented. “I’ve never looked at Aida like this,” he says. “Well, only when I was in jail and the Israelis asked me to point out my house.”

He points out the camp’s seven different neighborhoods and the small squares kids now play soccer in since the Wall came up and divided the camp from the olive orchard.

The land where the Intercontinental Hotel is today also used to be the camp’s as a space of play. The Intercontinental bought the land and built additional wings in the back, as well as a swimming pool, erecting its own wall, also separating itself while also taking land. This took place during 1996 or 1997, when Aida still had the olive orchard until Israel’s Apartheid Wall took that, too.

Mohammad likes the idea of mapping the camp’s everyday life and stares at the photograph for a while before he has to run. He is being asked to give an impromptu tour of Aida to a bus full of tourists.

I return to the Unity Tent in Manger Square. It is 6pm by now, and the sun is going down. I see OPG right away and ask what he thinks about the sit-in. He says he thinks it’s great.

“Any u’malaa’?” I ask. Any spies?

“No, it’s good!” He laughs.

He introduces me to a young man named N who gives a Palestine for beginners teach-in. I listen quietly, taking note that the most interesting analyses he is keeping to himself. When I think we are more comfortable with each other, I ask what he thinks about the March 15 Movement’s demands that Oslo be dissolved.

He replies, “Well, earlier this week in Ramallah a 15-year-old boy said out loud in the protests ‘Let’s end Oslo!’ and the police arrested him for that.”

“Ah, I won’t ask you anymore what you think then,” I smile and he laughs.

He mentions that a couple of people had been on a hunger strike, but that ended today when Mahmoud Abbas visited Ismail Haniyeh in Gaza.

He also reports that Afteem and the other falafel shop in Manger Square are handing out free food to everyone at the sit-in, without even a request from the protesters.

Night falls. As I leave Manger Square and head home, I notice a man has been following me.

22.

There was a bombing in the West Jerusalem Israeli bus station that killed a middle-aged Israeli woman.

The corporate press is reporting it has “destroyed years of relative calm” in Jerusalem, by which they mean “calm” only for the Israelis.

Israel’s daily violence in Jerusalem’s Palestinian neighborhoods of Sheikh Jarrah, Silwan, and Shuafat Refugee Camp, the dispossession, brutalization, arrests, house demolitions, and assassinations of Palestinians in Jerusalem are not mentioned as destroying the calm.

Salaam Fayyad, Mahmoud Abbas, the United States, the United Nations, and European Union quickly condemned the bombing in Jerusalem.

From Salaam Fayyad, Mahmoud Abbas, the United States, the United Nations, and the European Union, no condemnations had come the day before, when Israel killed eight people in Gaza.

23.

Today, I am accompanying Nidal north to Jenin Refugee Camp. Jenin is interested in learning more about the Aida mapping project and hopes to do a mapping workshop, too.

Nidal goes to Jenin every Saturday to conduct a democracy workshop with youth at one of the women’s organizations called “Not to Forget.” He says he’s using one of Naji Al-’Ali’s cartoons to talk about individualism and community.

Naji Al-’Ali was a political cartoonist and creator of Handala, the 10-year-old refugee boy who keeps his back turned to the world and his arms behind him refusing handouts, demanding nothing less than the return to Palestine.

Al-’Ali’s cartoons were critical of the collaborationist Arab regimes in addition to the regimes of Israel and the West, for which he was gunned down in London in 1987 with suspicion falling on Israel, Palestinian agents acting on behalf of Israel, and Palestinian agents acting on behalf of the Arab regimes.

Nidal recently held this workshop at Lajee Center, leading Aida’s youth to storm Salah’s office, demanding more democracy at Lajee, more participation in the decision-making processes. “Salah wasn’t impressed,” Nidal smiled about his friend.

I met up with Nidal at 8am at the main station so we could take a servis to Ramallah, a seven-passenger transport van that leaves as soon as all seven seats are filled. From there, we switch to a different servis to Jenin. We need to be in Jenin by noon, and the ride is about three hours. We easily make it through Wadi Al-Nar, arrive in Ramallah, and I marvel that my motion sickness never came. Maybe because we were talking the whole time.

Nidal invites me to eat falafel right as we land in Ramallah. He always eats falafel on such trips, he says, it holds the stomach together, so you don’t throw up.

On the third floor of the bus station, as we’re eating our falafel, Nidal points down to the vegetable market. I peer over and witness garlic, cucumbers, strawberries, onions, cauliflower arranged neatly in their stands. Most of the vegetables come from Jericho and Jenin, he says, and by noon the market is so packed, you can’t see the ground.

The road to Jenin is very green right now. It is Springtime and it’s been raining a lot, some parts are even reminding me of Guatemala where it rains a lot.

On the road to Nablus from Ramallah, Nidal points to where there used to be a checkpoint. It’s now been removed because a shepherd in the hills of Silwad would shoot at the soldiers, picking them off like a sniper. He killed 11 of them at the checkpoint, one by one, and the official Zionist militia had no idea who was shooting at them the whole time. The shepherd was a great shot, using an old rifle from the Second World War, whose ammunition puzzled the Zionists. They were convinced it had to be a European shooting at them. Each time after he was done taking his shot, the shepherd would hide the rifle in the fields and walk away to tend his flock. His entire operation was, in the end, successful, leading Israel to fully dismantle the checkpoint, and nobody ever found out. Then one day the shepherd told the story to some friends, and one of them turned out to be a collaborator. The shepherd was caught and arrested and has become a legend since. The legend of the Silwad Sniper.

We pass Nablus and arrive in Jenin early and head to the vegetable market. Nidal’s mother needs a vegetable called ‘akub, expensive in Bethlehem like the price of meat, but cheaper in Jenin since it grows in nearby Nablus. The vegetable market had no ‘akub for it was the end of the season. But Nidal asked around and found a man who had some in the back, then he haggled over the price, a lot. People started crowding to see the ‘akub. There was still ‘akub!

So today I met ‘akub, who is quite punk with thorns and stems and leaves that shoot out in different directions, and little heads that look like small artichokes. In the end, Nidal was able to get 7 kilos for 120 shekels.

We arrive at Jenin Camp and Nidal introduces me. I describe to the youth and coordinators the Aida Camp mapping project, and the coordinator, Mostahm Salameh, seems to love it. I show her the aerial photograph of Aida, and Mostahm recognizes it right away, “This is the map the Israelis use to intimidate us when we come in for interrogation.”

Mostahm is Belgian and Palestinian and speaks French, Arabic, and English. We brainstorm the different maps that could be made of Jenin Camp. For example, the stories of the massacre, the rebuilding of the camp after the roads were made wide enough for tanks to fit in… She loves the project and wants to learn the software. In the meantime, she’s going to find out if the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) or the camp’s popular committee have any existing maps or aerial photography we can work from.

On our way back to Bethlehem, Nidal tells me there are secret alleys you can’t see from above in the aerial photograph, and he’s eager to start mapping it. He also shares the story of when the Israelis shot him from a helicopter, right before Israel’s siege on the Church of the Nativity in 2002. Nidal was injured in his leg and had to go through a hellish experience to get to a hospital with curfews and checkpoints. He had to hide out in other peoples’ homes in the camp for over 30 days until the Israelis left.

I ask Nidal about his memories of when Israel built the Apartheid Wall. It was also during Israel’s siege on the Nativity Church. Everyone thought the Israelis were just plowing land for a road for their tanks, but then they started digging a trench. It was after Israel had already started that Israel officially announced its plans. That’s how the Apartheid Wall began, how the olive orchard was taken from Aida Camp, and how restricting Palestinian access to Jerusalem became easier for Israel.

We arrive in Ramallah and jump into a Bethlehem servis. As we get close to a big Israeli settlement, Ma’ale Adumim, Nidal points out the pine trees, which Israel plants on top of the destroyed villages. Pine trees grow quickly and cover the crime scene faster than other trees. They are planted where they’re not meant to be, like on Mount Carmel where they flared up last year when an Israeli kid’s argeela coal sparked the Haifa fire.

“At least they didn’t steal the olive tree from you,” I say.

“What do you mean they didn’t steal the olive tree,” he replies, “hold on just a moment.”

We pass Ma’ale Adumim at a highway roundabout, and Nidal points to the massive olive tree in the middle. “When they built the Wall, they took that tree from Aida Camp,” he says. A tree that used to be part of an orchard now stands alone, encircled on all sides by moving vehicles, in the middle of a circle of colored gravel. It taunts every Palestinian who has to pass it about what Israel is able to get away with.

“Every time I see it,” he says as we pass the tree, “I want to burn it.”

24.

Rachelle calls her friends Shaddi and Jihad to sit with us in Manger Square. Everybody owes a lot of electricity since the Second Intifada, Shaddi mentions to us as they sit. A lot of people haven’t been able to pay their electric bill. It hasn’t been a problem but recently they’ve begun electricity cuts. People are getting desperate and have begun selling their land, Shaddi says. “To other Palestinians,” he clarifies.

Shaddi has forgotten we have met before, and Rachelle tries to help him remember. He asks what I am doing in Palestine and we start talking about maps.

Jihad, who has up until now been sitting, smoking, uninterested, becomes interested. He has an old Greek map of Palestine, he says, and would I be able to read it? There is a church on that map called Saint Francis that doesn’t exist anymore.

I ask if he can draw it, and he draws a sword pointing down with two snakes, one on each side. He also draws a triangle with the number 20 on each edge. I ask him what that is. He says he has seen it on the ground, that there are thousands all over Palestine.

A survey benchmark, we together realize, where surveyors stick their instruments into ground to survey and map the land. The British colonizers did this to Palestine in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Shaddi and Jihad say they can show me where they are, if I want to see. Palestinians find all kinds of things they don’t let foreigners know about, unless they trust them. There’s gold and buried treasure. They share that Palestinians find relics from the Greek and Ottoman period that they then sell to get money, which they have to do since nobody can find a job. They sell the Greek artifacts to the Greeks, and the Ottoman ones to the Turks. Jihad says, “It’s part of their history.”

“What’s part of Palestinian history?” I ask.

“All of this stuff is not Palestinian history. It’s the occupiers’ history,” says Jihad. “We have been occupied by Israel, then the Romans, then the Greeks, then the Turks, then the British, and then Israel.”

“So, what would you consider Palestinian artifacts?” I ask the Palestine from below.

“Well, just little things nobody wants to pay for.”

There is a set of identical triplets on Star Street. I learned about them when I first arrived, thinking they were twins when only two of them came into Mary’s store.

“La’,” Mary had corrected me, held up three fingers, and ticked each one off as she said their names, “Musa, Issa, Mohammed.” Each named after a prophet of three sibling worlds: Judaism’s Moses, Christianity’s Jesus, Islam’s Mohammed. Identical triplets, ten years old.

For almost nine months I have lived on Star Street, and I have never once seen all three at the same time. Only two at the same time, sometimes only one.

One of them, when he is by himself, always makes faces and tries to whack me. I fight back though.

But walking home on Star Street tonight, I finally encounter the nabi-triplets, the prophet-triplets, heading straight toward me.

We are about to pass each other, and I fully expect the one who hates me to throw something at me, but he instead hands it to me. It is a flower. His name is Mohammad, he says, as we introduce ourselves.

I get to meet Issa, and nod. I meet Musa and tell him abu jozi is named Musa, too, making him smile.

There is another little boy there. I introduce myself. He has a name I’ve never heard of and I forget it right away.

I thank them for the flower and ask where it came from.

“Al-ezbaala,” they answer, the trash. I can only laugh.

As I say good night and turn to walk home, one of the triplets picks up more flowers from the ground and throws them at me. I now know it is Issa who doesn’t like me.

Mohammad picks up one of the flowers Issa threw down and hands it to me, so now I have two flowers, both from Mohammad.

I walk home delighted. I have finally seen the nabi triplets, all three prophets, all three identical, all at the same time.

And more than that, Mohammad and Musa have set a better example for Issa now, inshallah. Maybe next time we cross each other’s paths, Issa and I will greet each other instead of fight.